Charles Kelleway. The Test cricketer

Jim Cattlin and Ronald Cardwell have released a new book called “The Pupil and the Master – Charles Kelleway and Victor Trumper” which is the story of Charles Kelleway, the celebrated, Test, NSW and Gordon grade cricketer and the influence of Victor Trumper working its way through his early years. Trumper was the legend and Kelleway perhaps the pauper, yet they demonstrated on the cricket field and beyond the picket fences qualities that endear them to you. This is Charles Kelleway’s story with the influence of a legendary master, Victor Thomas Trumper.

The book is available for sale and detail can be found below.

Charles Kelleway was born in Lismore and played in 26 Test matches for Australia in the years 1910 to 1928. He initially made his name with New South Wales, before starting his Test career when South Africa first visited Australia in 1910. A very sound batsman, invaluable for opening the innings or facing a crisis, he possessed unlimited patience combined with a limited but effective range of shots. His bowling, by contrast, was lively and animated. Tall, with a loping run and high delivery, he bowled with good length and swerve. He seldom bowled two balls from the same angle, and he troubled the best batsmen.

Charles first played against England in the 1911 season, when the team captained by P. F. Warner won four of the five Tests. Kelleway’s best effort in eight innings was 70 and six wickets cost him 41.50 apiece; but coming back to England in 1912 he made 360 runs in six Test matches, with 114 at Manchester and 102 at Lord’s.

As the First World war approached Charles, along with his good friend Charlie Macartney, with whom he had played his first 15 Tests, began holding enlistment gatherings in the city, where they were encouraging players to sign up. Names of enlisted players were even being supplied to The Referee newspaper on a club by club basis by cricket officials. This was somehow intended to create a competition between the clubs to see who had the highest number of recruits.

One of the few shots of Charles in action

Charles enlisted on 1 June 1915, and entered the war in March 1916 in time for the Battle of the Somme. As one of a handful of Test cricketers in the war, and considered a celebrity by the sports-mad nation, Charles definitely didn’t shirk his duties, being a front line infantry soldier with the 1st Battalion. He was also wounded on two occasions, the first time in July 1916 when he attended the 3rd London General Hospital at the same time as four other present and future Gordon cricketers, William Prior, Claude Tozer, Johnnie Moyes and Harry Renshaw. Charles also knew Bert Oldfield well as Bert lived at 19 Allen Street Glebe Point and Charles at 23 Allen Street. Was it any wonder that so many Test and first class cricketers moved to the district and joined Gordon. Maybe the Gordon committee acted as their estate agents?

Charles remained in England after the war and played the first nine matches of the AIF Australian team’s tour of the UK. While he had been appointed captain before his controversial departure from the team, he had already indicated he wanted to go home in June and only missed a few remaining matches of the tour. While Charles had said it was his decision to return maybe it was more the actions of the General Officer Commanding the Australian troops, Field Marshall William Birdwood, who called in Herbert ‘Herbie’ Collins to take over the captaincy of the tour and was quoted as saying:

Kelleway is a good cricketer, but unfortunately he quarrels. I understand that he has already had three arguments, including one with a caretaker. I’m sending him back on the next ship.

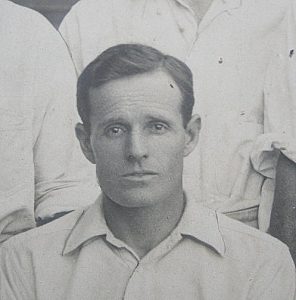

Charles in a Gordon team photo

Charles was one of only a handful of cricketers who played Test cricket both before and after the war, with a gap between 1912 and 1920. Of his twenty-six Tests, fifteen were played before the war and eleven after. He finished with 1,422 runs at 37.42 plus 52 wickets with his medium fast bowling.

The following is an extract from a book by Johnnie Moyes about Charles Kelleway:

If we accept the idea that Test match cricketers are born, Charles Kelleway was the exception to the rule. Without any natural advantages he made himself a particularly useful player by consistent practice, perseverance, and courage. As a batsman he lacked any touch of style and was as stiff-shouldered as a man who suffers from rheumatism. Forearms, rather than wrists, moved his bat into position, and he was almost ungainly in his footwork. Here was a solid toiler, without inspiration who, even when he made runs – and he did that often enough- gave no thrill to the onlooker. If he got one himself; he showed no signs of it, and to watch him was mostly to be bored. Yet when the day was over and the time for reflection came, the value of his innings could be assessed, often highly.

On his return to Australia, his health deteriorated and he often spent months at a time on the sick list.

Joining Gordon in 1922-23, Charles played a major role in the Club’s premiership victory in the following season when he scored 653 runs at an average of 81.63 and took 37 wickets at 15.03. Prior to the last two rounds, his figures were astonishing – 633 runs at 105.60 and 37 wickets at 12.00.

Charles became the fourth Gordon player to appear in a Test match while a member of the Club, when he was selected in the Australian team for the First Test against the touring English team in December 1924. Macartney, Trumper and Johnny Taylor were the first three.

Charles played an average of nine matches per season for Gordon over a period of twelve seasons from 1922 to 1933, collecting 3,441 runs at 45.88 and taking 220 wickets at 18.87. Charles retired from grade cricket after the 1933-34 season at the same time as Charlie Macartney when both were not far short of their 48th birthdays. His average of 45.88 places him third on Gordon’s all-time list of First Grade averages and in exalted company. Those above him are two of Australia’s all-time great batsmen, Vic Trumper and Charlie Macartney. Incidentally, the fourth highest average of 41.07 is held by Harry Evans.

Charles married Ethel Lee in 1922 and they had one son. He became involved in cricket administration after he finished playing and after a long illness died in 1944 at Lindfield at the age of fifty-eight.

Paul Stephenson

Book sale details

Below is a form with purchase details for the book